![]()

Peace Chief Topinabee

(Toop-Peen-Bee/Thu-pe-ne-bu/Tuthinipee/Topeeneebee/Topenibe/Topanepee/Topinabee/Topnibe/Topinebe/Topinebi/Topineby)

"He Who Sits Quietly"

"Sits Quietly"

Principal Chief of the Potawatomis

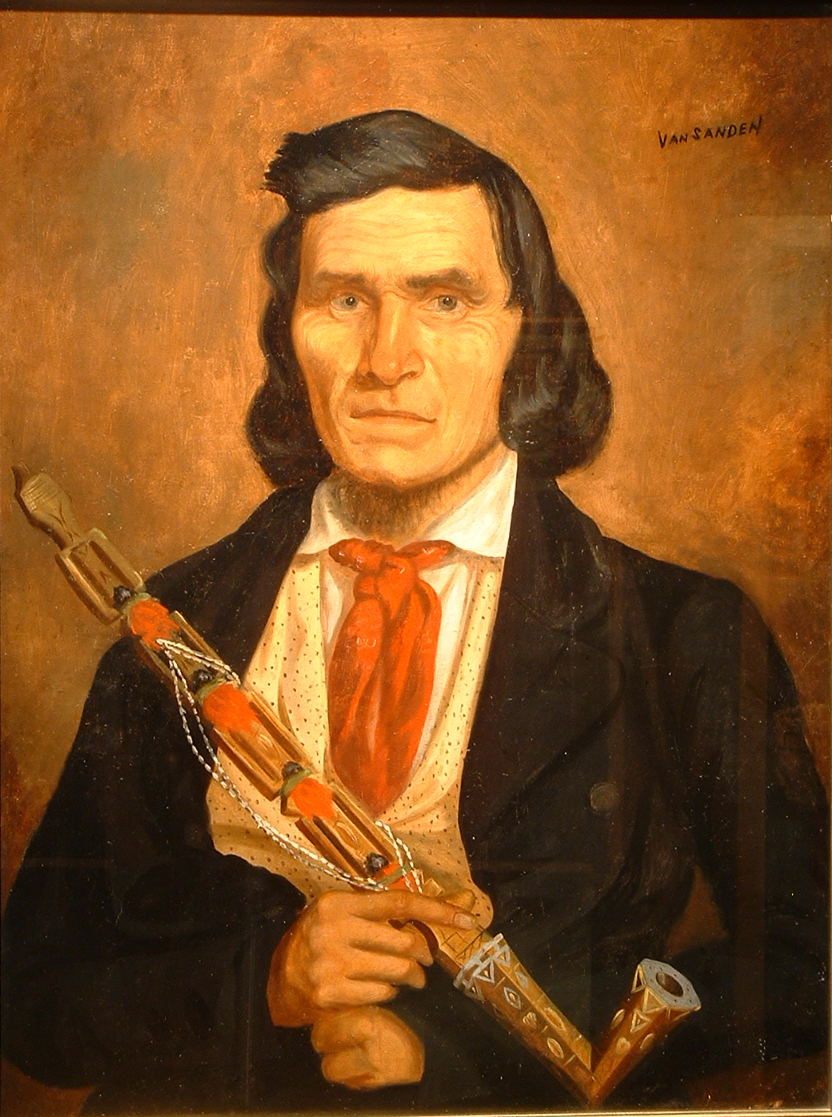

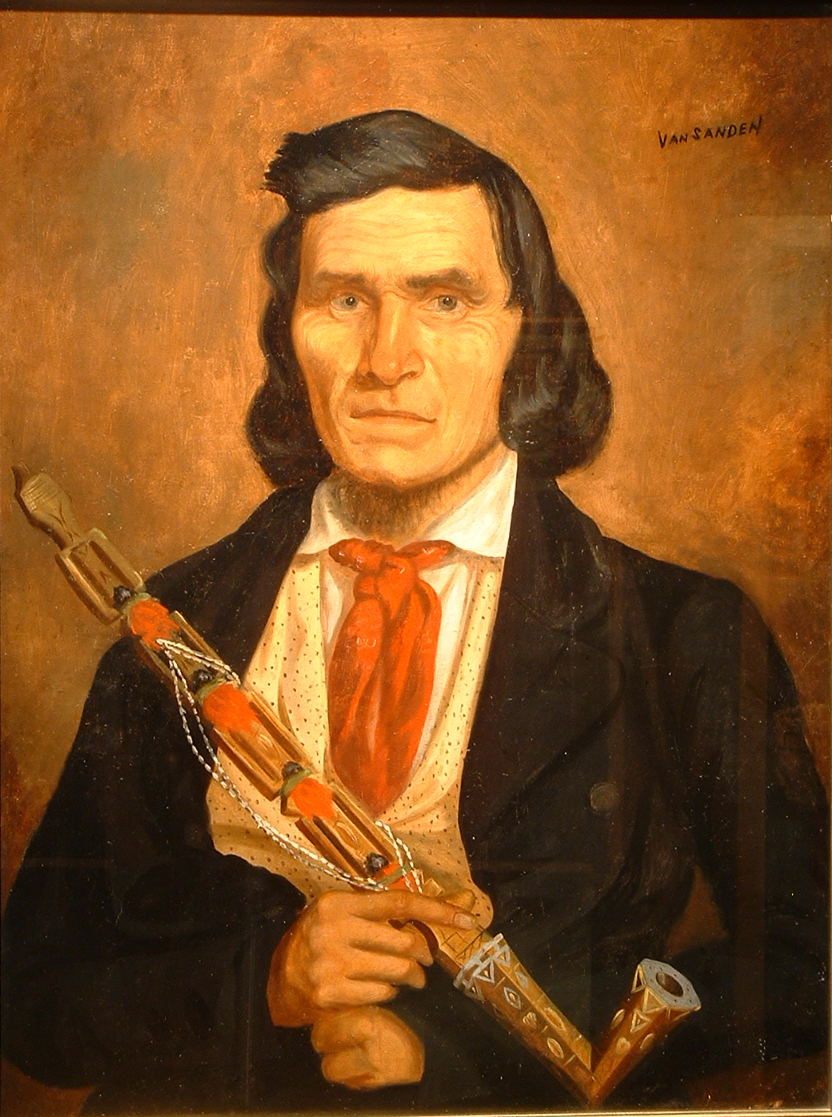

Chief Topinabee (He Who Sits Quietly). Next to his father, Old Chief Nanaquiba, he was also noted as one of the greatest Potawatomi chiefs of all time. He was born in his father’s village on the St. Joseph River in 1758. He was documented as a great warrior and known for his great tactical decisions in many battles like his father.

Above: Potawatomi Chief Topinabee. Painting of Chief Topinabee c. 1800 - c. 1820.

Chief Topinabee pipe and pipe stem is decorated with purple and white wampum shell beads. The feather amulets upon the pipe stem are from the heads and beaks of the Lady Amherst pheasant which is native to southwestern China and Myanmar (northern Burma) and later was introduced into Britain. Lady Amherst, the bird is named after Sarah, Countess of Amherst (1762 - 1838). Her husband William Pitt Amherst, governor general of India, was responsible for sending the first birds to London in the early 1800s. The Pheasant known as Lady Amherst was soon on route to America where the feathers were introduced to Native Americans for trade. These feathers can also be seen on headdresses or the body as decoration within Great Lakes native culture. Such birds were highly prized by Indian leaders, showing status and rank. They decorated their bodies and religious objects sometimes with feathers others were not always able to obtain.

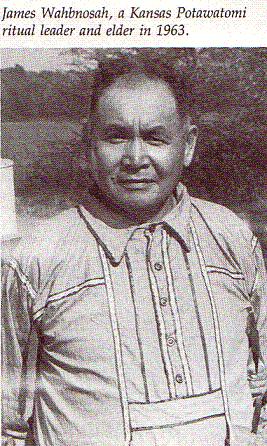

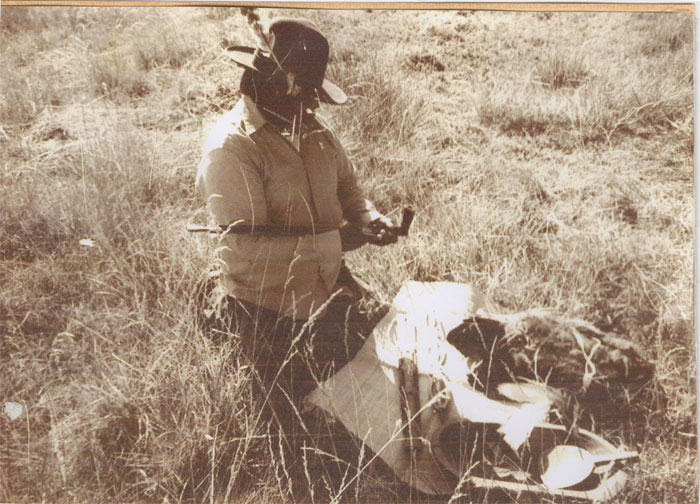

Above: James Wahbnosah, son of Wis-Ki-Ge-Amatyuk and Rosann Lasley Ke-O-Ko-Mo-Quah Potts, on the Prairie Band Reservation, 1963.

Photo taken by James A. Clifton for his book titled "Indians of North America: The Potawatomi". He is a cultural anthropologist and a leading authority on the ethnohistory of the Indians of the Great Lakes - Ohio Valley area. He is Frankenthal Professor of Anthropology and History at the University of Wisconsin, Green Bay, and previously taught at the Universities of Oregon, Colorado, and Kansas. He earned a Ph.B. at the University of Chicago and a Ph.D. at the University of Oregon.

![]()

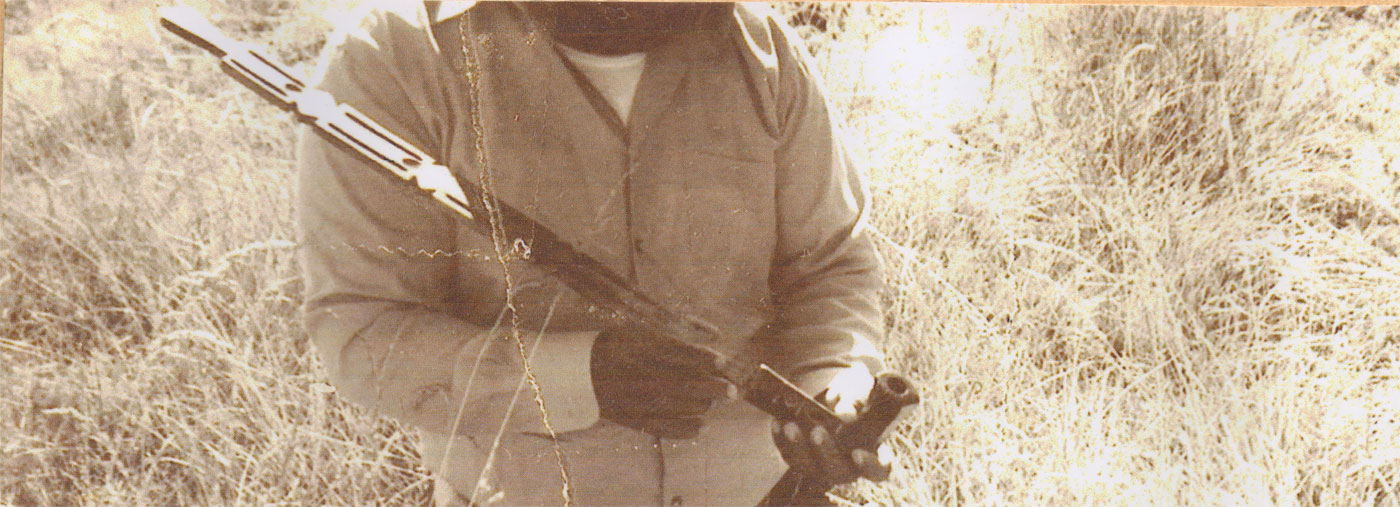

Below: Photograph of James Wahb-No-Sah. Photographs were taken by Ruth Landes on the Prairie Band Reservation in 1951. Ruth Landes was an American cultural anthropologist who studied the religious and cultural beliefs of the Prairie Potawatomis of Kansas. She also studied the rapid changes in their cultural and political environment. Ruth Landes conducted field work amongst the Prairie Potawatomi Indians on the Prairie Band Indian Reservaion in Kansas during 1935, 1936, and later in the 1950s and 1960s.

Above: James Wahb-No-Sah, son of Wis-Ki-Ge-Amatuk, Potawatomi Holyman and Principal Pipe Carrier. 1951 on the Prairie Band Potawatomi Reservation holds the original pipe and pipe stem of Chief Topinabee. It was said by James Wahb-No-Sah that the mouth piece of the Topinabee pipe stem had broken off due to frailty during his time of guardianship and had to be cared for and tended to correctly as it was not appropriate to leave the mouth piece of the traditional old stem broken. In the photo on the rush mat is the buffalo bundle, a Greenville Treaty pipe stem, and Chief Chebaas' pipe stem

These religious Potawatomi artifacts remained for decades within a small circle of traditionals on the Prairie Band reservation for ceremonial gatherings. Later, they were handed down to James Wahb-No-Sah, son Gary Wis-Ki-Ge-Amatyuk Sr., and have remained in the family since.

Above: The old pipe stem bears traditional Potawatomi marks of ancient fire starting. This traditional Neshnaabe pipe was used historically in counsils of great importance to the keeper of the fire.

![]()

Chief Topinabee was known to have 4 biological children, three sons and one daughter: Topinabee Jr., Wab-Sai, Mah-Zhee, and Elizabeth. Elizabeth, daughter of Chief Topinabee, was the wife of Chief Leopold Pokagon. Their child's name was Chief Simon Pokagon.

Above: Chief Leopold Pokagon, husband of Elizabeth Topinabee and father of Chief Simon Pokagon

Above: Chief Simon Pokagon, son of Chief Leopold Pokagon and Elizabeth Topinabee

Chief Topinabee was a main signer of all important treaties. He first appeared on the official document called the Treaty of Greene Ville in 1795. His name was written as “Thu-pe-ne-bu”. Most of the Potawatomis arrived in Ohio during the first week of July 1795. The official treaty negotiations began on July 15, 1795. The Treaty of Greene Ville was documented as one of the most historic gatherings of peace between twelve dominant tribes and the United States. The Potawatomis were the second largest in number of warriors and chiefs, with a total of 340. The Delaware's attendance was 381. Documented treaty attendants were 180 Wyandot, 381 Delaware, 143 Shawnee, 45 Ottawa, 10 Kickapoo and Kaskaskia, 46 Chippewa, 340 Potawatomis, 73 Miami and Eel River, 12 Wea and Piankeshaw on August 3, 1795. During this ceremonial gathering, Chief Topinabee (Thupenebu), was present along with Chief Little Turtle of the Miami and other tribal leaders to seek resolutions for a peace with the Americans. Chief Topinabee and Chief Little Turtle would find themselves together in the following years negotiating once again. Following the 1795 treaty signing, many continued a peace with the Long Knives (Americans), releasing American prisoners. But British influence amongst the Potawatomis would continue to alarm the Americans as many Potawatomis remained friendly to the British as they received many gifts and trade goods.

Attempting to counter British influence, the Americans launched a program of their own. Potawatomis visiting Detroit or Ft. Wayne were provided food and presents in an effort to impress the Potawatomis and their neighbors with the power and numbers of their great white father. The government decided to send a delegation of chiefs to Philadelphia. On October 4, 1796, Chief Topinabee and Chief Five Medals accompanied by leaders from the Shawnees, Miamis, Ottawas, Chippewas, and Wabash tribes set sail from Detroit on board the Schooner (Swan) escorted by a group of government agents and interpreters. The Indians arrived in Philadelphia late November. There they met with President George Washington who presided at a banquet and then spoke formally to the assembled tribesmen. President George Washington reminded all the Indians, including the Potawatomis, of the terms in the Treaty of Greene Ville and urged them to relinquish hunting in favor of agriculture. President George Washington also acknowledged that the whites had committed crimes against the Indians, and promised that their actions would be punished. In return, the Potawatomis and other Indians were to turn over those tribesmen responsible for crimes against the whites.

After the meeting with President Washington, the Potawatomis and other Indians returned to their homes. The chiefs' impressions of President Washington remains unknown. President George Washington's suggestions on agriculture seemed to interest the chiefs, especially Chief Five Medals, for when he returned home to Indiana, he found many of his Potawatomi band hungry and ill prepared for the winter. The fur trade was declining throughout the Potawatomi homeland and game was scarce. Although the Indians still planted gardens, their meager stores of corn and beans could not sustain them through the cold months. Between 1796 and 1801, the Potawatomis in northern Indiana and southern Michigan suffered poor winter hunts and Chief Five Medals became convinced that the tribe's economic woes could only be cured through farming.

By 1800, Chief Five Medals had pursuaded Chief Topinabee that the Potawatomis should ask the government for agricultural assistance. In late 1801, Chief Topinabee and Chief Five Medals of the Potawatomis accompanied Chief Little Turtle of the Miamis along with several other Indian leaders to Washington. On the way to the capitol, the party passed through Baltimore where they met with a convention of Quakers dedicated to missions on the western frontier. In December 1801, Chief Five Medals addressed the convention and informed the friends that the Potawatomis were interested in agriculture, but they needed guidance in clearing lands and establishing farms. The Indians asked the Quakers for assistance and much to the audience's delight, denounced the burgeoning whiskey trade as an evil being forced on them by unscrupulous traders.

Chief Topinabee, Chief Little Turle, and Chief Five Medals, along with others would continue their travels to Washington where they met with government officials in January 1802. In the capitol, Chief Little Turtle spoke for all the tribes including the Potawatomis and again asked for government assistance in establishing farms. The Miami chief also asked officials to keep whites from settling on Indian territory, especially those areas bordering the government lands at Vincennes. He complained that the governments annuity goods were often of a poor quality and asked that the Miami and Potawatomis annuities be paid at Ft. Wayne instead of Detroit. Finally, the Miami chief pleaded that the government suppress the liquor trade, which he described as a fatal poison amongst the tribes of the Wabash Valley.

Chief Little Turtle's complaints over annuity distribution were strongly supported by Chief Topinabee and Chief Five Medals. Since the Potawatomis received their annuities in Detroit, many of the villages failed to share in the goods. Tribesmen from Illinois, Wisconsin, and along the Tippecanoe were isolated from the distribution center and rarely obtained any money and merchandise. By moving the annuity payment to Ft. Wayne, the distribution would be more centrally located, although the Illinois and Wisconsin tribesmen would still be forced to travel great distances.

Chief Topinabee and Chief Five Medals also were concerned about other problems mentioned by Chief Little Turtle. Although the flow of illegal whiskey had not reached their homes in floodtide proportions, the liquor trade along the Wabash continually increased and the more responsible chiefs wanted to limits the quantity. Chief Little Turtle's speech obviously pleased both President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of War, Henry Dearborn. They assured the Indians that their grievances would be ameliorated, and President Jefferson was especially gratified over the request for farming equipment. Responsible chiefs such as Topinabee, attempted to limit the traffic of whiskey, but they were unsuccessful and warriors full of whiskey were hard to control. Although Chief Topinabee and Chief Five Medals had railed against the use of liquor, they in time would like so many of their tribesmen be addicted to it. The demand for whiskey was so great that both British and American traders used it as a standard commodity in the fur trade. Chief Topinabee and his Potawatomis resented the liquor traffics debilitating effect upon their people and they blamed the United States government.

Historically, Chief Topinabee of the Potawatomis had lived through and dealt with the first six presidents in the shaping of the United States: George Washington 1789-1797, John Adams 1797-1801, Thomas Jefferson 1801-1809, James Madison 1809-1817, James Monroe 1817-1825, John Adams 1825-1829. Chief Topinabee, great and intelligent chief of the Potawatomis, lived and fought for the rights of his people to secure and better their futures. Chief Topinabee passed on to the spirit world in sadness as he knew his people's futures would be unknown as their situations as a Native people seemed to only become worse at the hands of the United States government.

Chief Topinabee's village on the St. Joseph River was called N’Do Waw Goyuk. The world of the Neshnaabe Potawatomi Nation was changing drastically through battles and war over land. But the drink known as Ish-Kot-E-Wabo (Fire Water or whiskey) would destroy the people in many different ways. The introduction of alcohol was a major changing point for the Potawatomis. It was a bad medicine that most of the Indians felt took over the mind and body like a bad spirit. The drink was addicting and many natives thirsted for this new drink that would slowly destroy them individually. In the first introduction of alcohol to the Potawatomis, it was known that Chief Topinabee was truly against the whiskey as he seen it took the warriors minds away and they would often begin fighting amongst each other. But it was known that as time went by and for reasons unknown, Chief Topinabee, a great chief of his people, was drawn to the Ish-Kot-E-Wabo (Fire Water or whiskey). Some historians believe depression took to the old chief as his people’s world was changing quickly.

Topinabee was a trusted friend to the whites, but his only fault being his thirst for liquor, a habit that was undoing. When at the treaty of Chicago, General Cass told him to keep sober so that he might secure a good bargain for himself and for his people. But under the influence of the horrible drink and not thinking, he replied, “Father, we do not care for the land, nor the money, nor the goods. What we want is whiskey, give us whiskey.” Many chiefs and warriors fell victim to the strength of the drink that would bring so many problems to the people.

The Reverend Isaac McCoy records the death of Topinabee, one of the principal chiefs of the Potawatomis, on July 27, 1826 as follows: “The principal chief fell from his horse under influence of ardent spirits, and received an injury of which he died two days afterwards.” Chief Topinabee died near present day Niles, Michigan. Chief Topinabee was the brother to Chief Chebaas and Kaukema (Cakimi) Burnett.

The name of To-pen-i-be was last carried traditionally by two biological descendants. They were believed to be the children of Topinabee Jr. They lived upon the prairie band Potawatomi reserve of Kansas. They are documented within the Prairie Band Allottees Rolls. They were last noted as dead, and land sold.

![]()

The following are excerpts from a book called, "Gateway to Empire," by Allan W. Eckert of Topinabee's role in "the struggle to control the "gateway to empire" - the Chicago Portage, the vital link between the east and the untapped riches of the west":

"Gateway to Empire" is fact, not fiction. The incidents described here actually occurred; the dates are historically accurate; the characters, regardless of how major or how minor, actually lived the roles in which they are portrayed."

![]()

(Below is from the year 1774, "Gateway to Empire," by Allan W. Eckert, p.21)

"....Some of the new traders treated the Indians with fairness and respect, and those few prospered. One such was William Burnett, who began his trading out of Detroit but soon moved his headquarters to the St. Joseph River a few miles from the old French village called Petit Coeur de Cerf. The site he selected was the largest Potawatomi village in this region and its leader, Topenebe, one of the most powerful and influential of the Potawatomi chiefs. Not only did Burnett and Topenebe become close friends, the trader soon married the chief's sister, Kawkeeme, and the Potawatomies accepted him as one of their own....."

![]()

(Below is from the year 1778, "Gateway to Empire," by Allan W. Eckert, pp. 52-54)

Introduction of friendship between William Burnett, John Kinzie, and Chief Topenebe

"....Within a week of his arrival in Detroit, John had become an habitué of the Detroit branch of William Burnett's business in the Indian trade. Soon he met Burnett himself, a dour man married to the sister of the powerful Potawatomi chief named Topenebe. Burnett was among the best established and most skilled and respected of the Indian traders; skilled and respected not only by his own countrymen, but equally but the Indians with whom he dealt. At a time when cheating Indians in trade was all but endemic, William Burnett was a rock of fairness. It was that, as much as anything, that encouraged John to seek employment from Burnett.

Young Kinzie went to work for William Burnett within mere weeks of his arrival in Detroit, mostly at the Detroit post, but occasionally at the trader's principal post adjacent adjacent to Topenebe's village on the St. Joseph River, almost two hundred miles west along the Potawatomi Trail....."

"....As he had learned swiftly and well the trade of the silversmith from George Farnham, so now young Kinzie began rapidly absorbing the more obscure elements of Indian trade from Burnett. Before long he met Burnett's Potawatomi wife, Kawkeeme-an overflowing barrel of a woman with jolly manner that masked an unusually sharp mind. She liked John Kinzie immediately and introduced him to her famed brother.

In Topenebe, John Kinzie encountered for the first time a man possessing not only great personal magnetism and even an aura of charisma, but one with remarkably developed leadershop abilities. If the Potawatomi tribe had had a principal chief, as did many other tribes, chances were good that Topenebe would have filled that seat. Such, however, was not the status of the tribe. Very widely spread over the land in disparate concentrations since the destruction of the Illinois Confederacy, the Potawatomi tribe was comprised of bands which, in a general way, cooperated with one another in most matters, but which occasionally differed in matters of great importance....."

"....John and Topenebe had an immediate affinity for one another, which quickly grew into a strong mutual friendship and respect. When merely as a matter of friendship and esteem and neither asking nor expection anything in return, John presented him with a beautifully fashioned and brilliantly polished silver gorget upon which he had engraved a wreath of oak leaves and acorns encircling a pipe tomahawk, the effusive gratitude of Topenebe was downright embarrassing. As of that moment, Topenebe had become John's champion and protector....."

"....A little matter had occurred only recently that pleased John about as much as anything that had happened since his arrival here. He had been given a Potawatomi name by Chief Topenebe and practically overnight he was being addressed by this name by all the Potawatomi with whom he had contact, and by a great many of the Ottawas and Chippewas as well. The name was Shawneeawkee-The Silver Man."

![]()

(Below is from the year 1798, "Gateway to Empire," by Allan W. Eckert, pp. 263-264)

Physical description of William Burnett and Chief Topenebe and origin of Chief Topenebe's name

"....the scents of lamp oil and green wood and, prervading all, the scent of wood-smoke from the Ben Franklin stove.

The two men greeted John Kinzie, one of them a heavy-set man if medium height with poorly trimmed dark hair shot with gray and bushy mustache and eyebrows to match. He wore a desreputable ankle-length greatcoat of mcuh-stained dark gray wool and his fet were clad in heavy outer moccasins. His face was fleshy and the small dark eyes porcine, yet not repugnant. He appeared to be in his late fifties and, despite his unkept appearance, he swept off his wolfskin cap and made a courtly bow to Eleanor and Margaret when John introduced them. This was William Burnett.

The second man was tall and craggy, clad in leggins and wrapped about with a heavy green woolen blanket. His eyes were large, dark, faintly almond-shaped, couched above unusually prominent cheekbones. On his head he wore a broad red band, from the rear of which projected five eagle feathers, two pointing upward and three down. He was an impressive figure and even before the introduction, Eleanor knew it had to be the prominent Potawatomi chief, Topenebe.

The chief stretched out his arms toward her, hand held palm down. Not knowing how to respond, Eleanor reached out and placed her hand against his, palm up. It seemed to take Topenebe by surprise and the corners of his mouth twitched.

"You...are...welcome," he said in a deep, measured pace.

"Thank you," said Eleanor, dipping slightly and withdrawing her hand.

John Kinzie and William Burnett were grinning. "Topenebe only knows two English sentences," the latter chuckled. "'You are welcome' and 'You go away now.' Looks like you've evoked the favorable one. Well, you are welcome here. Been a long time since a lady such as yourself graced this area. We've been looking forward to meeting you ever since John first told us about you last fall. We hope your stay here will be long and happy."

The two men then turned their attention to Little Margaret, gravely shook her hand and welcomed her, and John Kinzie laughed aloud. Normally Margaret McKillip was garrulous and very outgoing, but on this occasion, more than merely shy, she was nonplussed. She'd seen Indians before, but Topenebe was the first she had actually met and her gaze was locked on him. Finally she looked away and spoke to the older trader.

"Mr. Burnett, you said he doesn't speak English except a little. Will you ask him a question for me?" When Burnett nodded, she went on. "Will you ask him to tell me what the name Topenebe means and how he got it?"

"I can probably tell you that myself, little lady," Burnett said, "but I'll relay the question so he can answer in his own words." He turned and broke into a brief guttural monologue to the Potawatomi chief. As he finished, Topenebe threw back his head and laughed aloud. He spoke to her in his own tongue, watching her closely and, when he finished, he kept his eyes on her as Burnett interpreted.

"My name, Topenebe, means 'He-Who-Sits-Quietly,' or sometimes just 'Sits-Quietly.' It was given to me by my parents because I did not cry as most other babies did, I just sat quietly. I still most often do so."

Topenebe listened as Burnett spoke to him again, replied briefly and lapsed into silence with a small smile on his lips. Burnett turned back to Margaret. "He says, 'I am glad for what you have said. You are my friend.' And I have to add this, little lady," Burnett continued, speaking for himself, "That's the first time I;ve ever known Topenebe to call someone a friend on such short acquaintance. Looks as if you've made an important conquest. It'll never hurt you to have Topenebe's friendship."...."

![]()

(Below is from the year 1803, "Gateway to Empire," by Allan W. Eckert, pp. 309-312)

The feelings, emotions, and temper of Chief Topenebe

" ...."I had once hoped that our people could learn how to make the land give up food to us,' Topenebe said, sipping from his brandy glass, "but I see not that this will not be. To try to replace our traditional hunting and farming is, to them, only a different way for the white man to come into their country and change it. And cows and pigs do not take the place of buffalo and elk and deer for us. Our people will not-"

He broke off and turned around as the door to the trading post opened and a short man entered. Both were surprised to see that it was Jean Lalime. There was an aura of contained excitement in the little man's manner as he greeted the two and then told John Kinzie that he had merely stopped by while en route to Detroit. ..."

With studied nonchalance he went on to say that he had temporarily closed up the store at Chicago and was now heading for Detroit "...to make arrangements with the merchants there to supply my post with goods of valud to the military." There was a peculiar arrogance in his manner and John Kinzie frowned and held up a hand.

"Twice," he commented, "you have referred to the Chicago establishment as your post, in a manner which suggests you actually feel it is your post. I remind you that you are my agent at the Chicago store and that is all. As for becoming suttler to the fort, it is my own intention to become just that when Mrs. Kinzie and I arrive next spring to take over the situation there."

"you can't," Lalime said tightly, drawing himself up to his full five feet four inches. "It is my post. I am legal owner on the bill of sale."

John Kinzie scowled, hardly believing what he was hearing. "Whatever you're trying to pull here, Lalime, it won't work. You acted only as my agent and with my money in the purchase of that post from Du Sable."

Topenebe had been looking back and forth between the men, not understanding the words but clearly reading the heat rising between them. He held up a hand. "Speak in my tongue," he demanded.

John nodded and repeated in Potawatomi what Lalime had said and his own response. Topenebe's features hardened as he listened and then he spoke quietly to Lalime.

"When you worked in the trade at Mackinac, you were not always fair in your dealings with the Indians and eventually they drove you away. You cam here and you were not fair with us here and we were glad to see you go away. Now you are at Chicago and I am told by Black Partridge that his people are not happy with how you are trading with them. Beware."

John Kinzie strode to a desk and brought out paper and quill. "You agreed," he told Lalime, still speaking in Potawatomi, "when you acted as my agent in the purchase of Du Sable's post, to run it as I wished it run, to treat the Indians fairly and to sign the post over to me on my demand." He dipped the quill and wrote swiftly on the sheet, blotted it and then straightened. "I now make that demand. This," he tapped the paper with a forefinger, "states that the Chicago post is now and always has been, since its purchase from Du Sable, mine. Sign it."

Lalime shook his head. "It's legally recorded in my name, remember? It's my post." His hand was resting on the tomahawk in his belt. His nostrils flared above the thick black moustache and his narrowed eyes were locked on John, so he was unprepared for Topenebe's swift movement.

The Potawatomi chief took a quick step forward and his hands shot out. One gripped the wrist of the hand poised on the tomahawk and pinned the arm at his side. The other gripped Lalime's long hair and twisted, jerking his head backward and pulling him off balance. Before he could recover he was pulled down, with the small of his back across Topenebe's knee and the chief's face hovering over his.

"you lie!" the Potawatomi hissed. "I do not care what the papers say. You forget I was there. I saw. I heard. You have gotten away with cheating Indians in small ways. You will not get away with cheating my friend in a big way. Do you wish Nokenoqua to sing the death song for her husband? You will sign Shawneeawkee's paper now or, I promise you, what I hold in my hand," he jerked the hair savagely, "will hang in my lodge this night!"

Topenebe pulled Lalime's hand away from the tomahawk and he snatched the weapon out of the man's belt, then thrust him away. Lalime rolled over on the floor and came to his feet in a crouch in the same movement. His eyes were filled with fear as he looked from Topenebe to Kinzie and then back to Topenebe again. The Potawatomi stared at him scornfully and merely tilted his head toward his trader friend.

Lalime straightened slowly, carefully in his actions, and moved to the desk. He signed the paper with such force that on the final stroke the point of the quill collapsed and caused a blot. It made no difference. Kinzie didn't even look at it.

"Get out," he said flatly. "Don't come back. You're no longer working for me and you're through in Chicago."

Lalime glared at him and then walked quickly toward the door. Topenebe flicked his wrist and Lalime's tomahawk sped through the air and buried itself on the inside of the door just as Lalime reached it. The man stopped, facing the door, body taut.

"Take your toy with you," Topenebe said, his tone of voice mocking. "If you ever see me again, be prepared to use it. If you can."

Lalime reached out and wrenched the tomahawk free and returned it to his belt, still facing away from them. Then he opened the door and turned on the threshold. He didn't look at the Potawatomi, only at the trader.

"We'll see whether or not I'm through in Chicago," he said in English, his words hardly more than a raspy whisper. "One of these days, Kinzie, I'll kill you."

Then he was gone. ..."